Offering concepts for a more inclusive Delhi: In the words of Gautam Bhan

Offering concepts for a more inclusive Delhi: In the words of Gautam Bhan

Mukta Naik, Delhi Community Manager

Delhi, 9 June 2016

In your recent book, you pose questions around inequality and persistence of poverty ‘from’ Delhi, not ‘of’ Delhi. Does each city then pose its own unique questions?

Place matters, particularly in the construction of what comes to be known as ‘urban theory.’ Right now, this is the sum of a series of particular inquiries asked from very particular places. Could we consider it as the sum of a series of particular inquires asked from different places?

Delhi has something to say about planning, law, inequality, slums, evictions, illegality, form, and citizenship. So do Sao Paulo, Cairo, Johannesburg and Dhaka. When these cities take the concepts as they emerge from here, do they have better a conceptual armory to understand their cities than the terms inherited from the industrial landscapes of the North? That’s what remains to be seen. That’s the conversation the book is a part of.

Do you believe it is possible for citizens to be serious stakeholders in the process of planning and reshaping Delhi? How?

Do you believe it is possible for citizens to be serious stakeholders in the process of planning and reshaping Delhi? How?

I think citizens of Delhi are already serious stakeholders in planning and shaping the city – just not in formal, legible ways. I think the paucity lies in our ability to understand these different landscapes of “participation”: from patterns of (il)legal, unexpected use to public and organized resistance; from structural changes in democratic politics and formal representation to shifting landscapes of corruption; from the way the Metro has created new social and physical geographies of circulation and aesthetics to the brute symbolism of the Commonwealth Games – the list is endless. I think the city is at a saturation and excess of participation – it’s just not going to play by the rules of some formal process where participation is contained, bound by rules and made to behave. So the question is: at a time when the city is buzzing with dynamism – are we able to listen, read and support the ways in which citizens are shaping the processes of planning and re-shaping Delhi?

You point out that our understanding of urban issues are shaped by the contexts in the Global South. Yet in India, policymakers and city planners continue to borrow from the North when they seek solutions. How could this change?

There are two things at stake here: whether we have the right knowledge to offer, and whether we are offering it in ways that can translate into practice. I think both are significant challenges. If we don’t want our policymakers to use concepts from the North, we must ask – what are the concepts we are offering in their place?

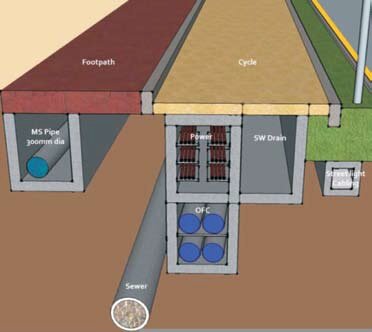

This is why I think the creation of new and more appropriate frameworks is so important. I want to understand informality not because I have a theoretical bone to pick, but so that we can then figure modes of practice, ways of moving forward. So, again, from our cities, we can ask: If you practice in a city that is auto-constructed, that was built outside planning, then how do you plan? If the concept of “regulation” loses its familiar meanings because your public institutions have no history of enforcement, how do you try and intervene into a land market, an urban form, an economic assemblage, a city? Where are the courses on retrofit and repair in our architectural colleges or the courses on post-facto planning in our planning departments? What is “network” or “trunk” infrastructure in a city already built and running on a patchwork of decentralized provisions with a range of legalities? How do you imagine economic development if informality is not a transitionary stage in “modernization” but a medium-term condition? What is a politics of urban welfare that is not premised on labor as a foundational pillar of citizenship? What is neoliberalism if a state never provided for it to then “withdraw?” We have to also offer ways of moving forward that are provisional, not silver bullet; incremental, not all-knowing. Both these tasks lie before us.

What measures could Delhi take to include its under-provided citizens?

The first is that Delhi, because of its city-state like nature and its history of public land ownership, has the ability to regulate its land markets more than other cities. Leveraging public land can alter the economic, spatial and financial landscape of this city and tilt towards more equitable outcomes in housing, employment, public space and even environmental services. Yet within the current political economy of value, a serious political shift in thinking has to be fought for us to move in this direction.

The second, because I work most closely in housing, is to take seriously the realities of our housing crisis. The simple fact is this: the only affordable housing built at scale by any actor in our city is the housing auto-constructed by communities and people. This housing, however, is often structurally inadequate (though it, incrementally, usually grows to standard), and is marked by insecure tenure. Two decades of evictions have shown precisely how insecure such de facto tenure regimes are. Yet our policy approach is to build its way out of this mess, with the magical 25 square meter flat as the mass produced silver bullet. Nothing suggests that we can do this. Nothing suggests that we should – that this new vertical housing will be desired, viable, sustainable or, even at its most basic, occupied. Reversing our policy approach in housing to lessen the time it takes for incremental housing to become secure and adequate, and building on what people have already built through upgrading and universal service provision, is the only way forward. The longer we take to realize it, the more likely that another generation will inherit the vulnerabilities of their parents rather than the fruits of their lifetime of labor.

Last, Delhi must take seriously the need to construct a true urban welfare regime. This means both scaling rights and entitlements to the city and delivering them locally. The resources exist to do this, the mechanisms are less clearly understood and the political will is still fragile, though it is improving. Structuring this regime means expanding existing rights in education and food to health, shelter, and water. It also means taking seriously the way spatial illegality makes most city residents ineligible for rights – if you cant exist on paper legally either through employment or housing, you cannot effectively claim entitlements. Therefore, spatial illegality and economic informality combine in the auto-constructed city to de facto exclude claims to rights even when de jure rights exist. Innovations in delivery must follow the expansion of entitlements – Delhi has the ability to lead here, to expand welfare without waiting for the nation as we have done in much of Indian history has done.

Close.

Photo: Gautam Bhan

Permalink to this discussion: http://urb.im/c1606

Permalink to this post: http://urb.im/ca1606dle

June 2016 — This month, URB.im will talk to expert planners and architects from our network of global cities to better understand how cities can grow and develop more equitably. The world has seen extraordinary urban development over the last couple of decades, and while cities have become centers of economic growth, those gains haven't been felt by all residents equally. Haphazard development and planning has left many emerging cities in a state of chaos. Our experts discuss the current situation in their cities, some key policies and programs that could be harnessed for improved development and ideas for moving ahead with more coordinated action. Join our exciting discussion!

June 2016 — This month, URB.im will talk to expert planners and architects from our network of global cities to better understand how cities can grow and develop more equitably. The world has seen extraordinary urban development over the last couple of decades, and while cities have become centers of economic growth, those gains haven't been felt by all residents equally. Haphazard development and planning has left many emerging cities in a state of chaos. Our experts discuss the current situation in their cities, some key policies and programs that could be harnessed for improved development and ideas for moving ahead with more coordinated action. Join our exciting discussion!

Eduarda La Rocque e seu pacto por um Rio melhor

Eduarda La Rocque e seu pacto por um Rio melhor

Qui hoạch thành phố hợp lí hơn từ những bước đi đầu tiên

Qui hoạch thành phố hợp lí hơn từ những bước đi đầu tiên

Como construir cidades igualitárias?

Como construir cidades igualitárias?

On Closing the Inequality Gap in Accra: With urban planner Victoria Okoye

On Closing the Inequality Gap in Accra: With urban planner Victoria Okoye

Can Dar es Salaam Grow Equitably? A town planner responds.

Can Dar es Salaam Grow Equitably? A town planner responds.

Interactive and Incremental Processes and Possibilities: An interview with Monica Albonico of Albonico Sack Metacity

Interactive and Incremental Processes and Possibilities: An interview with Monica Albonico of Albonico Sack Metacity What are the key values and ideas that you work with, and what kinds of environments do you seek to achieve with it?

What are the key values and ideas that you work with, and what kinds of environments do you seek to achieve with it?

عن النوع الإجتماعي والمدينة: لقاء صحفي مع المعمارية عبد المحيي

عن النوع الإجتماعي والمدينة: لقاء صحفي مع المعمارية عبد المحيي

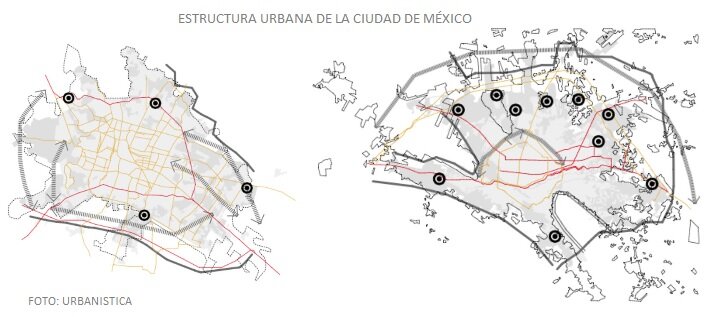

Planeación Urbana en la CDMX con Urbanisto Salvador Herrera

Planeación Urbana en la CDMX con Urbanisto Salvador Herrera

El Papel de los Equipamientos Urbanos en Cali: Una entrevista a Angela María Franco Calderón

El Papel de los Equipamientos Urbanos en Cali: Una entrevista a Angela María Franco Calderón ¿Existe desde la Alcaldía una visión global de este tema? ¿puede el sector privado jugar un papel destacado?

¿Existe desde la Alcaldía una visión global de este tema? ¿puede el sector privado jugar un papel destacado?

Surabaya: Menuju Kota yang Berkeadilan dengan E-Government

Surabaya: Menuju Kota yang Berkeadilan dengan E-Government

Bengaluru is India's most livable city, but is it equitable?

Bengaluru is India's most livable city, but is it equitable?

Entrevista con Elisa Silva

Entrevista con Elisa Silva

Offering concepts for a more inclusive Delhi: In the words of Gautam Bhan

Offering concepts for a more inclusive Delhi: In the words of Gautam Bhan Do you believe it is possible for citizens to be serious stakeholders in the process of planning and reshaping Delhi? How?

Do you believe it is possible for citizens to be serious stakeholders in the process of planning and reshaping Delhi? How?

Expert View on a New Lagos: an interview with Olufemi Olarewaju

Expert View on a New Lagos: an interview with Olufemi Olarewaju How can Lagos grow more equitably?

How can Lagos grow more equitably?

Discussing Chittagong’s urban future with Prof. Hoque

Discussing Chittagong’s urban future with Prof. Hoque What are the biggest challenges that Chittagong faces in terms of equitability?

What are the biggest challenges that Chittagong faces in terms of equitability?

Urbanista Nadia Somekh: "A cidade é o lugar para a democracia direta"

Urbanista Nadia Somekh: "A cidade é o lugar para a democracia direta" Teoria

Teoria

Will Mumbai maximize its new development plan?

Will Mumbai maximize its new development plan? This month, we speak with Hussain Indorewala, a faculty member at the Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, who also writes about urban politics, sustainability, and planning in Mumbai, about the potential of the plan in its current state.

This month, we speak with Hussain Indorewala, a faculty member at the Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies, who also writes about urban politics, sustainability, and planning in Mumbai, about the potential of the plan in its current state.

Comments

Will Mumbai maximize its new development plan?

Dear Ashali

Nice interview. I wonder why your interviewee did not refer to the safe places or venues for women and marginalized communities in the DP, and in general does the DP considers green zones for children and families sporting for example given the threats against women in a city as Mumbai?

Best regards,

Shaima

Asentamientos informales

Ana Cristina, muy interesante el artículo; me parece que la publicación del libro sobre asentamientos informales en Caracas es indispensable para identificar las condiciones en las que vive la población vulnerable, las necesidades y sobre todo georreferenciar en donde se encuentran asentados para poder reubicarlos. En la Ciudad de México tenemos un problema común con los asentamientos, no obstante hay escasez de uso de suelo para el desarrollo de viviendas y requiere de implementar estrategias integrales para la reubicación de los asentados. De igual manera, en el artículo de la Ciudad de México, Salvador Herrera comenta que es necesario impulsar la vivienda social en las residencias existentes.

Will Mumbai maximize its new development plan?

Dear Shaima,

I tried to keep the interview general and concise and thus never explicitly asked about women and safe spaces in the city. The recently released Revised Draft Development Plan 2034 has allocated a few pages to "Gender, Special Groups and Social Equity" which includes stipulations for amenity provision dedicated for women. Among these amenities are multipurpose housing for working women, vending areas for women, public toilets, and care/skill centres for women and families. Many groups in the city feel that this is inadequate and it doesn't necessarily discuss gender or women outside the context of working women. However, said groups do feel that it's a step in the right direction.

Cheers,

Ashali

Will Mumbai maximize its new development plan?

Thanks a lot Ashali for the detailed answer. Great that gender is mainstreamed through the new development plan anyway :)

All Success,

Shaima

Add new comment